If you asked me what foods I’d like to make, I wouldn’t give you a list straight away. I’d give you a story. Because to me, food is never just food. It is memory, inheritance, longing, and love. It is the soft language of care when words don’t come easily. It is how I miss people, how I remember them, and sometimes, how I forgive them.

I’d start with the dishes of my childhood. The kind that took hours to make, and seconds to vanish from the table.

Sinigang would be the first. That tamarind-sour soup that feels like a soft slap and a warm hug at the same time. I want to learn how to make it the way my Lola did—perfectly balanced, the broth almost medicinal in its comfort. When life turns too sweet or too bitter, sinigang reminds you that it’s okay to be in between—to sit with the sourness, and still rise full.

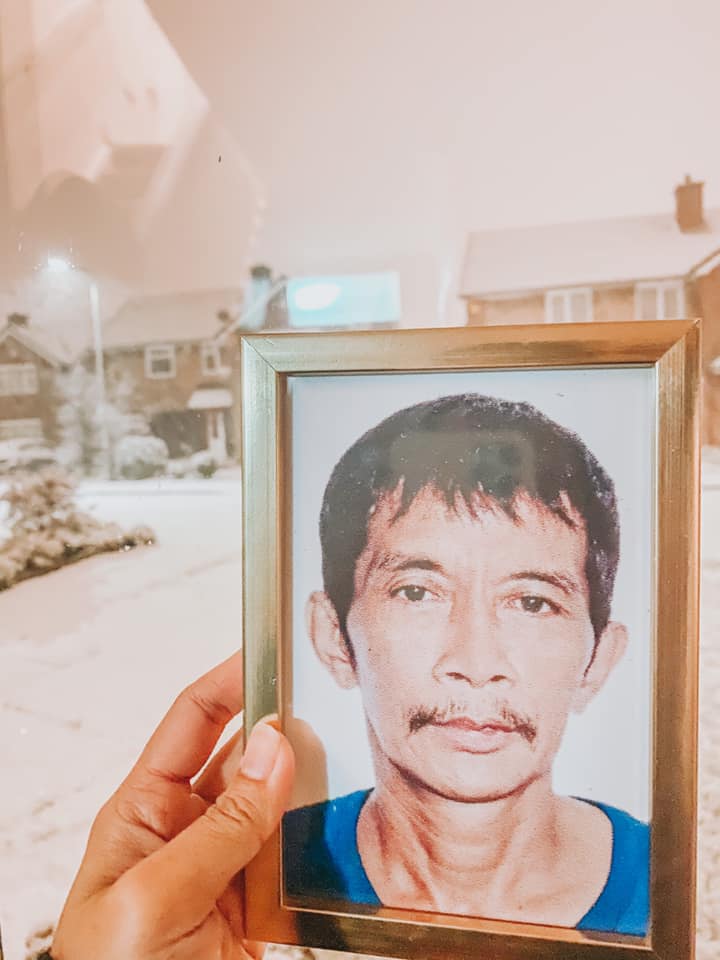

I’d like to master adobo, but not just any adobo. My mother’s adobo. The one that turns meat into poetry. I still remember the smell of garlic and soy sauce filling our house while I did my homework on the kitchen table. There was a rhythm to her movements, a quiet assurance that she knew exactly how long to simmer, how much vinegar to pour—not too little that it fades, not too much that it overpowers. I never asked for the recipe. I wish I had. But maybe that’s the lesson: some things are taught not by words, but by presence. By watching. By being near.

Pancit bihon, of course—for birthdays, graduations, and reunions. Because where I’m from, long noodles mean long life. And even if it tangles sometimes, you keep slurping through. That’s life, isn’t it? A mess of salty-sweet-sour moments you have to chew through with faith.

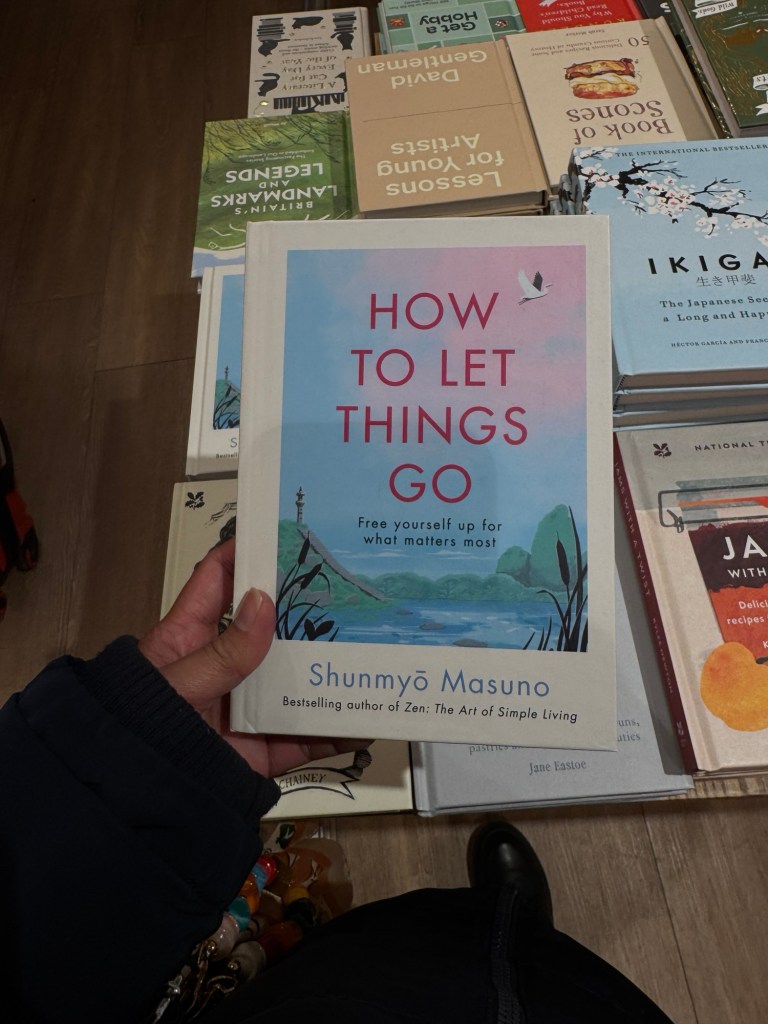

But more than the classics, I want to learn things that aren’t mine—yet.

I want to stretch beyond nostalgia and into possibility.

One day, I hope to try making homemade pasta—the kind where you roll the dough by hand and hang it like laundry across your kitchen. Because there’s something grounding about creating food slowly, in a world that rushes everything. It teaches patience. It teaches care. It teaches you to stay with a task, even when your arms ache and your flour-covered fingers can’t feel your phone.

I’d like to bake sourdough bread too. Not because it’s trendy, but because it’s alive. A sourdough starter is like faith—it needs feeding, nurturing, time. You can’t microwave it into existence. You wait. You watch. You believe it will rise.

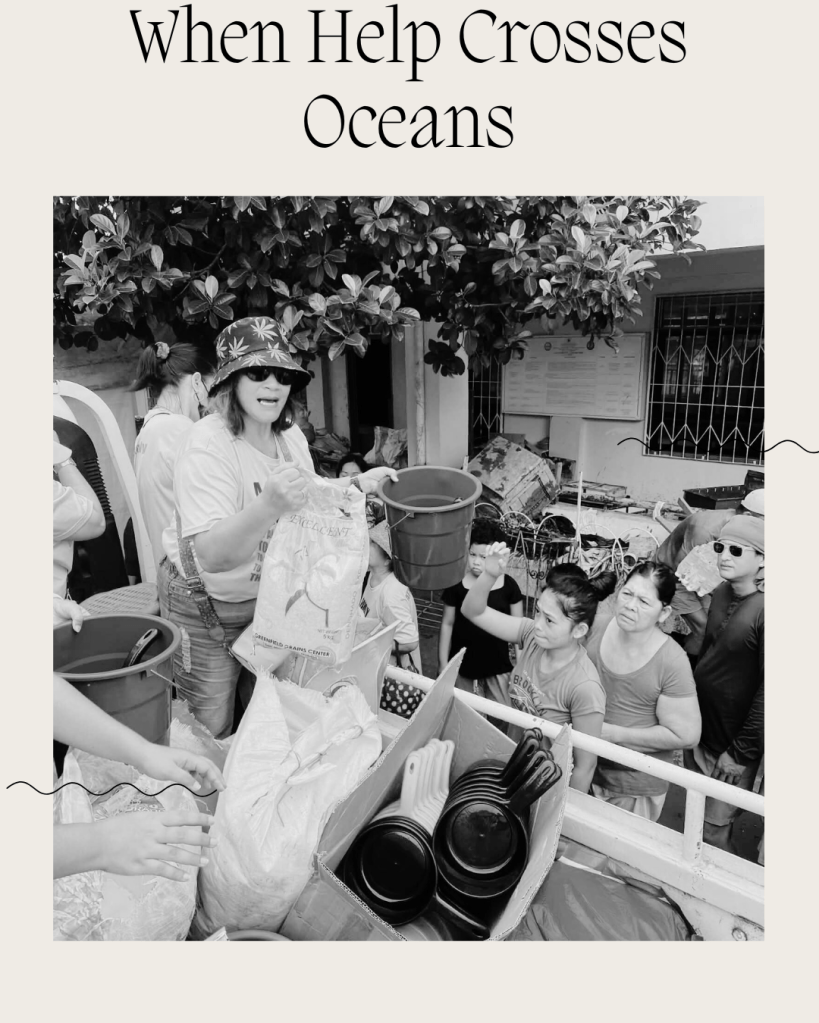

And then, there’s krumkake—a Norwegian treat I’ve never tasted, but dream of making someday. My fiancé’s heritage carries flavors I don’t yet fully understand, but I want to. I want to learn the language of his childhood—through flour, through cream, through the delicate lace of a cookie that whispers stories from a different land. Love, after all, is learning what feeds the other person’s soul—and then trying to make it with your own two hands.

More than any one dish, I want to make food that feels like coming home.

I want to cook meals that hold silence gently, that bring laughter back to the room, that taste like “I’ve been thinking about you.”

I want to cook for friends who are grieving, for family I haven’t seen in years, for a future child who will one day ask, “What does home taste like?”

Because here’s what I’ve come to believe:

To cook is to love. To feed someone is to say, “You matter.”

It doesn’t always take a perfect recipe. Just a willing heart, a clean spoon, and a little faith that something warm and good can still come out of a world that feels cold sometimes.

I’ll say:

The kind that nourish the body and the memory.

The kind that soften the edges of a hard day.

The kind that remind someone—even if just for a bite or two—that they are held, loved, and never truly alone.

Leave a comment